I cringe a little at the term data science. It conveys all the hype and false-promise you’d expect of an occupation recently described as the “sexiest job of the 21st century“. It’s all-encompassing, yet it manages to describe little in its vagueness.

The ambiguity of its definition will probably resolve itself in time. But the ambiguity surrounding its potential applications deserves more attention and debate. The question is whether data science will come to be associated more with proprietary tools of companies like Google, as a weapon for the NSA, or more broadly as a way of improving and participating in social cooperation and self-governance.

Data science has attracted a healthy share of doubts and criticism. Whatever its analytical and technological sophistication, its social merits are less clear.

The field is emerging at a time when large corporations, its first users and pushers, are at a dismally low point in public trust. Our governments meanwhile seem prone to using data science in ways that diminish trust and confidence. It’s not a good thing that so much of the general population was introduced to “metadata” in the context of the NSA collecting their phone records.

If there’s an area where government seems most set to use data science in the public interest, it’s at the city level. There are examples of forecasting devastating flash floods in Rio; plans for clean and efficient housing in Songdo, South Korea; designs for more efficient parking in Boston; tools for better responding to crime in Seattle; and apps for tracking snow-plows and pothole service requests in Chicago.

Yet along with these exciting and hopeful developments come concerns that we’re simply rushing toward the false promise of a ‘scientifically managed’ society that eventually degenerates into the self-interested rule of a new kind of narrow elite.

There’s something intuitively disconcerting about too much knowledge in the hands of too few. Scientific discovery certainly isn’t new. What distinguishes this historical moment from previous periods isn’t that a few of us make brilliant scientific discoveries. It’s that so many of us use and contribute to them; that new discoveries are being made by those who weren’t supposed to be making them.

The question then for data science is whether it furthers this democratization of science, whether it diffuses into our broader society – or becomes the exclusive preoccupation of yet another misguided technocratic elite.

As I understand it, that is a big part of why the Data Science for Social Good program was created. To understand why, let’s step back and unpack the term we’ve collectively chosen to define ourselves.

Data science, despite assertions to the contrary, is not just about big (or even little) data. Data is just observations that we’ve collected and made systematic enough to treat as multiple records of a single thing – home sales, bus trips, crime incidents, and so on. Science is a way of using these observations to learn about the world. And science works best when it’s cumulative and open.

The scientist and philosopher Michael Polanyi illustrated why in his paper The Republic of Science. Take a non-cumulative activity like a group of people shelling peas. They’re engaged in the same task, but their individual efforts don’t build on each other, so working in isolation won’t make them shell fewer peas. That’s true of a surprisingly significant amount of professional and public-oriented work. In contrast, coordination and cumulation are at the very core of scientific activity:

“Imagine that we have the pieces of a very large jigsaw puzzle, and that for some reason it’s important that our giant puzzle be put together as quickly as possible. We might try to work fastest by recruiting several helpers; the question would be how to structure the work.

Suppose we divide the puzzle pieces equally among the helpers and let each work on her set separately. It’s easy to see that this method, which would work fine for shelling peas, would be totally ineffective for the puzzle, since few of the pieces in each helper’s set would be found to fit together.

We could do better by providing duplicates of all the pieces to each helper separately, and eventually somehow bring their individual results together. But even with this approach the team wouldn’t be much better than the performance of a single individual at her best.

The only way the assistants can effectively cooperate, and thoroughly surpass what any single one of them could do, is to let them work on putting the puzzle together in sight of the others so that every time a piece is fitted in by one participant, all the others will immediately watch out for the next step that becomes possible in consequence. In this system, each participant will act on her own initiative, by responding to the latest achievements of the others, and the completion of their joint task will be greatly accelerated.”

The Data Science for Social Good program has recruited helpers. Our job is not only to complete projects that contribute to social good, but to work on them in a transparent way that contributes to society’s emerging understanding of what data science is and how it should work.

It’s not for us to work behind the tinted glass of Google buses on the way to Mountain View, or on proprietary algorithms that journalists fear will destroy creativity in Hollywood – although maybe we’re too late on that one.

While respecting privacy and confidentiality, our job is to work in the open as much as possible. It’s not enough to just have a “policy” of openness – we want our work to be as understandable and inspectable as possible. Our goal is to work in a way that invites replication, imitation, improvement, and even rejection.

The earliest example of this ethos involves Chicago’s open data portal, the City’s way of working in the open. This past December, Chicago’s Mayor Rahm Emanuel signed an executive order formalizing the city government’s commitment to helping the public become more informed about their city and about the work their government does. The core of that commitment is the city’s data portal.

The portal provides access to data about the buses Chicagoans ride, the books they read, the potholes they drive over, the salaries they pay their city officials, and much more. It holds 273 different datasets – some with only 30 rows, some with over five million.

However, for most users the portal is information overload. It’s meant to make data accessible, but the design doesn’t accomplish that purpose. It seemingly gives you everything you want right away, but it also gives you everything you don’t want.

As data science fellows, many of our projects begin with the data portal because that’s where the city, the partner for many of our projects, decided to put its data. If we leave it as is, we’ll have lost an opportunity for making data science more accessible. We’ll have failed to help citizens better access and understand the data we work with, and the data that increasingly informs government policies.

So I decided to create a map of the portal to give Chicagoans a better sense of what data the City has opened. I also wanted the map to be a better way for users to find specific data they’re interested in. And I wanted it to be a tool that both data scientists and everyone else might find useful – data science for social good means tools that can be shared by a diverse public, not just by an exclusive technocracy.

#chart {

width: 1000px;

height: 700px;

background: #bbb;

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

margin-bottom: 60px;

position: relative;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

text {

pointer-events: none;

}

.grandparent text { /* header text */

font-weight: bold;

font-size: medium;

font-family: "Open Sans", Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

}

rect {

fill: none;

stroke: #fff;

}

rect.parent,

.grandparent rect {

stroke-width: 2px;

}

.grandparent rect {

fill: #fff;

}

.children rect.parent,

.grandparent rect {

cursor: pointer;

}

rect.parent {

pointer-events: all;

}

.children:hover rect.child,

.grandparent:hover rect {

fill: #aaa;

}

.textdiv { /* text in the boxes */

font-size: x-small;

padding: 5px;

font-family: "Open Sans", Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;

}

After I published the map and opened up the underlying code, I got a response I hadn’t anticipated.

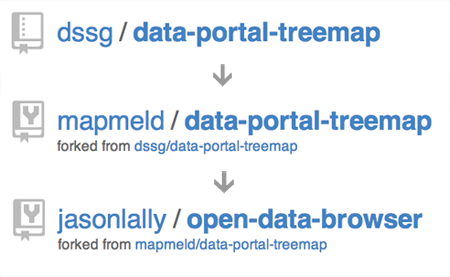

Within a day a couple of Code for America fellows had reused the code to build maps of Boston and San Francisco’s data portals. Jason Lally, an urban planner with Place Matters, substantially improved the way the map collects data about portals and built a map for every Socrata data portal.

What happened after I designed the first map illustrates why how we work is as important as what we work on. And it’s just a small example, among many others, of a principle much bigger than improving access to the Chicago city data portal.

The ethical imperative of doing data science in an open and inclusive way is fairly clear and intuitive. The scientific imperative is more easily forgotten.

Like jigsaw puzzles, research problems get solved faster and more efficiently when we work on them cumulatively. But more than that, wider participation by the public makes scientific advancements more likely. Much of the data that’s out there is largely useless. If we want better data, we’ll need more and different kinds of people participating in the collection and use of data.

Likewise, for data science to become a more positive part of society, we need more people to become active producers and informed users of data, not just passive consumers and unwitting surveillance targets.

Science in academia has too often forgotten the scientific importance of openness. Data science in business has only tangentially concerned itself with it. As data science continues to emerge as an important part of society and modern self-government, I’m excited that there are practitioners doing their best to demystify the field and keep it accessible.